Immigration and Emigration

페이지 정보

작성자 관리자 작성일작성일 11-12-13 수정일수정일 70-01-01 조회27,321회관련링크

본문

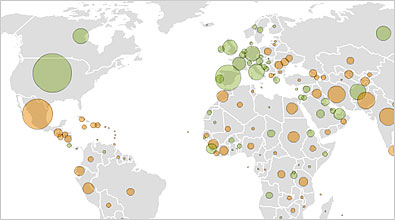

<Interactive Graphic: Global Migration>

Nearly 190 million people, about three percent of the world?s population, lived outside their country of birth in 2005. A look at the flow of people around the globe.

Immigration and Emigration

Updated: Dec. 12, 2011

There has been no significant movement toward federal immigration reform since a bipartisan effort died in 2007, blocked by conservative opposition. But it has been the subject of a fever of legislation at the state level, and it could become an issue in the 2012 presidential campaign.

In December 2011, The Supreme Court agreed to decide whether Arizona may impose tough anti-immigration measures. Among them, in a law enacted in 2010 and challenged by the Obama administration, is a requirement that police in Arizona question people they stop about their immigration status. The ramifications of the court’s decision for immigration policy; for other states; and possibly for presidential politics are far-reaching.

The Obama administration has steered clear of making a push for comprehensive legislation to address immigration reform. Instead, to the dismay of Hispanic supporters, the administration has focused on a stepped-up campaign of deportation. Yet the administration has made it clear that its goal is to quickly deport convicted criminals, while in many cases halting the deportation of illegal immigrants with no criminal record.

The Obama administration’s tough approach to law enforcement and deportation has met resistance even among its usual allies. Democratic Governors from Massachusetts, Illinois and New York — states with large immigrant populations — have decided not to participate in Secure Communities, a fingerprint-sharing program.

Speeding — or Suspending — Deportations

Showing the kinder, gentler side of the administration’s strategy, in August 2011, the White House announced that the Department of Homeland Security would, on a case-by-case basis, suspend deportation proceedings against people who posed no public safety threat. The policy shift has been criticized by some as a backdoor form of the so-called Dream Act — a bill, blocked by Republicans in Congress, that would provide relief to illegal immigrants who were brought to the United States as children and who want to attend college or join the armed forces.

A month later, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency announced that it had arrested 2,901 immigrants with criminal records, highlighting the flip side of the administration’s policy. Officials from the agency portrayed the seven-day sweep, called Operation Cross Check, as the largest enforcement and removal operation in its history. It involved arrests in all 50 states of criminal offenders of 115 nationalities, including people convicted of manslaughter, armed robbery, aggravated assault and sex crimes.

In keeping with both objectives, in November 2011, the Department of Homeland Security announced that it would begin a review of all deportation cases before the immigration courts and start a nationwide training program for enforcement agents and prosecuting lawyers, with the aim of speeding deportations of convicted criminals and halting those of many illegal immigrants with no criminal record.

Taken together, the review and the training, which will instruct immigration agents on closing deportations that fall outside the department’s priorities, are designed to bring sweeping changes to the immigration courts and to enforcement strategies of field agents nationwide.

The approach of deporting some illegal immigrants but not others requires a deep change in the mentality of agents, who have long operated on the principle that any violation was good cause for deportation.

Administration officials said they would proceed case by case using existing legal authorities, and had no plans to exempt any large group of illegal immigrants from deportation.

Background

From the time of the nation’s founding, immigration has been crucial to the United States’ growth and a periodic source of conflict. In recent decades, the country has experienced another great wave of immigration, the largest since the 1920s. However, for the first time, illegal immigrants outnumbered legal ones. The number of illegal immigrants peaked at an estimated 11.9 million in 2008. About 11.2 million illegal immigrants were living in the United States in 2010, a number essentially unchanged from the previous year, a 2011 study showed.

Republicans and Democrats have agreed for years on the need for sweeping changes in the federal immigration laws. President George W. Bush for three years pushed for a bipartisan bill before giving up in 2007 following an outcry from voters opposed to any path to legal status for illegal aliens. During the years that followed, the issue has mostly been dormant, as both parties have been wary of the divisive passions it can arouse.

Immigration Under Bush

In January 2004, President Bush called for an overhaul of the immigration laws, proposing the broadest changes since legislation in 1986 that gave amnesty to more than three million illegal immigrants. Mr. Bush asked Congress to create a guest worker program. Immigrants would be authorized as guest workers for three years, then required to return home. The plan offered illegal immigrants in this country the possibility of becoming legal by registering as temporary workers. After opening the debate, Mr. Bush did not press the issue during his re-election campaign that year.

By 2005, frustration was growing over illegal immigration, particularly among voters in states like Arizona and Georgia that had seen a surge in newcomers. In December 2005, the House passed a bill, championed by conservative Republicans, which focused on law enforcement and border security. Church groups and organizations representing immigrants and Hispanics protested the measure.

In May 2006, the Senate easily passed legislation — crafted primarily by the late Senator Edward M. Kennedy, Democrat of Massachusetts, and by Senator John McCain, Republican of Arizona — that offered a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants and created a guest worker program. But the differences with the House bill proved too great to bridge, and the legislation died. By October of that year Congress, reflecting the changing mood in the country, passed a bill ordering the construction by the end of 2008 of about 700 miles of border fences.

President Bush seized the initiative again in early 2007, convening negotiations among a small bipartisan group of lawmakers, this time including Senator John Kyl, Republican of Arizona, instead of Senator McCain. They wrote an ambitious bill, which was referred to as comprehensive reform, that proposed to open a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants after fees and other penalties, to create a guest worker program and also to re-orient the immigration system to put more emphasis on importing workers and less on family reunification.

That measure encountered intense opposition from well-organized voters who decried it as amnesty for immigrant lawbreakers. It died in June 2007 when it failed to attract enough votes to reach the Senate floor.

In the absence of federal legislation, state legislatures stepped in, adopting 206 laws related to immigration in 2008. The majority of new laws were designed to curb illegal immigration. However, some states sought to aid immigrants with programs to help them learn English and to speed their assimilation in other ways.

On a federal level, officials at Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a branch of the Department of Homeland Security, stepped up raids at factories and in communities.

Immigration Under Obama

Hispanic voters, including many newly naturalized immigrants, helped win several swing states for Barack Obama in 2008. Hispanic groups pressed President Obama to halt workplace raids and to move forward with legislation opening legal pathways for illegal immigrants. But despite early pledges to moderate the Bush administration’s tough policies, the Obama administration pursued an aggressive strategy for an illegal-immigration crackdown.

The Obama administration in August 2009 announced an ambitious plan to overhaul the much-criticized way the nation detains immigration violators, trying to transform it from a patchwork of jail and prison cells to what its new chief called a “truly civil detention system.” The plan aimed to establish more centralized authority over the system, and more direct oversight of detention centers that have come under fire for mistreatment of detainees and substandard — sometimes fatal — medical care.

The government stopped sending families to the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, a former state prison near Austin, Tex., that drew an American Civil Liberties Union lawsuit and scathing news coverage for putting young children behind razor wire.

The decision to stop sending families to Hutto, and to set aside plans for three new family detention centers, was the Obama administration’s clearest departure from its predecessor’s polices. Even so, the Obama administration has embraced many Bush administration policies, including expanding a program to verify worker immigration status that has been widely criticized, bolstering partnerships between federal immigration agents and local police departments, and rejecting a petition for legally binding rules on conditions in immigration detention.

In another enforcement change, the administration replaced immigration raids at factories and farms with a quieter enforcement strategy: sending federal agents to scour companies’ records for illegal immigrant workers.

While the sweeps of the past commonly led to the deportation of such workers, the “silent raids,” as employers call the audits, usually result in the workers being fired, but in many cases they are not deported.

Employers say the audits reach more companies than the work-site roundups of the administration of President George W. Bush. The audits force businesses to fire every suspected illegal immigrant on the payroll — not just those who happened to be on duty at the time of a raid — and make it much harder to hire other unauthorized workers as replacements.

After taking office, Mr. Obama repeated a campaign pledge to offer a comprehensive bill before the end of 2009, and he chose proponents of that approach for senior positions in the administration, notably Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano and Labor Secretary Hilda Solis. But the deep recession, with millions of Americans losing jobs, dimmed the political prospects for efforts to increase immigration, and groups opposing legalization remained confident they could block any such proposal.

In broad outlines, officials said, the Obama administration favored legislation that would bring illegal immigrants into the legal system by recognizing that they violated the law, and imposing fines and other penalties to fit the offense. The legislation would seek to prevent future illegal immigration by strengthening border enforcement and cracking down on employers who hire illegal immigrants, while creating a national system for verifying the legal immigration status of new workers.

Activity Swings Toward the States

With little movement toward federal immigration reform in recent years, individual states have churned out legislation.

Immigration certainly got the nation’s attention in 2010 after the passage of an Arizona statute. On July 28, 2010, one day before the law was to take effect, a federal judge blocked Arizona from enforcing the statute’s most controversial provisions, including sections that called for officers to check a person’s immigration status while enforcing other laws and that required immigrants to carry their papers at all times.

The Obama administration challenged parts of the law in court, saying that it could not be reconciled with federal immigration laws and policies. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, in San Francisco, blocked enforcement of parts of the law in April 2011. In December, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the Arizona case.

In urging the court to hear the case, Arizona v. United States, No. 11-182, Paul D. Clement, representing Arizona, said the state law did not conflict with but, rather, complemented federal policies. In a brief urging the Supreme Court not to hear the case, Donald B. Verrilli Jr., the United States solicitor general, said this provision created a state “crime of being unlawfully present in the United States.”

During the time that Arizona’s law was blocked, the center of activity on immigration moved elsewhere. Legislative leaders in at least half a dozen states said they would propose bills similar to Arizona’s law, and have announced measures to limit access to public colleges and other benefits for illegal immigrants and to punish employers who hire them. And at least five states have agreed on an unusual coordinated effort to cancel automatic United States citizenship for children born in this country to illegal immigrant parents.

Opponents say that the effort would be unconstitutional, arguing that the power to grant citizenship resides with the federal government, not with the states.

In September 2011, a federal judge upheld most sections of Alabama’s far-reaching immigration law that had been challenged by the Obama administration, including portions that had been blocked in other states.

The decision, by Judge Sharon Lovelace Blackburn of Federal District Court in Birmingham, made it more likely that the fate of the recent flurry of state laws against illegal immigration would be decided by the Supreme Court. It also means that Alabama now has by far the strictest such law of any state, going further than the one passed in Arizona.

The judge issued a preliminary injunction against several sections of the law, agreeing with the government’s case that they pre-empted federal law. She blocked a broad provision that outlawed the harboring or transporting of illegal immigrants and another that barred illegal immigrants from enrolling in or attending public universities.

The judge upheld a section that requires state and local law enforcement officials to try to verify a person’s immigration status during routine traffic stops or arrests, if “a reasonable suspicion” exists that the person is in the country illegally. And she ruled that a section that criminalized the “willful failure” of a person in the country illegally to carry federal immigration papers did not pre-empt federal law.

Privately Run Immigration Detention System

In the United States and elsewhere, including Britain and Australia, the use of private security companies has turned the detention of unwanted immigrants into a multinational industry. Increasingly, governments are looking to private companies to expand detention and show voters that they are enforcing tougher immigration laws.

Some of the companies are huge — one is among the largest private employers in the world — and they say they are meeting demand faster and less expensively than the public sector could.

But the ballooning of privatized detention has been accompanied by scathing inspection reports, lawsuits and the documentation of widespread abuse and neglect, sometimes lethal. Human rights groups say detention has neither worked as a deterrent nor speeded deportation, as governments contend, and some worry about the creation of a “detention-industrial complex” with a momentum of its own.

Private companies now control nearly half of all detention beds in the United States. In Britain, 7 of 11 detention centers and most short-term holding places for immigrants are run by for-profit contractors.

No country has more completely outsourced immigration enforcement, with more troubled results, than Australia. Under unusually severe mandatory detention laws, the system has been run by a succession of three publicly traded companies since 1998.

Nearly 190 million people, about three percent of the world?s population, lived outside their country of birth in 2005. A look at the flow of people around the globe.

Immigration and Emigration

Updated: Dec. 12, 2011

There has been no significant movement toward federal immigration reform since a bipartisan effort died in 2007, blocked by conservative opposition. But it has been the subject of a fever of legislation at the state level, and it could become an issue in the 2012 presidential campaign.

In December 2011, The Supreme Court agreed to decide whether Arizona may impose tough anti-immigration measures. Among them, in a law enacted in 2010 and challenged by the Obama administration, is a requirement that police in Arizona question people they stop about their immigration status. The ramifications of the court’s decision for immigration policy; for other states; and possibly for presidential politics are far-reaching.

The Obama administration has steered clear of making a push for comprehensive legislation to address immigration reform. Instead, to the dismay of Hispanic supporters, the administration has focused on a stepped-up campaign of deportation. Yet the administration has made it clear that its goal is to quickly deport convicted criminals, while in many cases halting the deportation of illegal immigrants with no criminal record.

The Obama administration’s tough approach to law enforcement and deportation has met resistance even among its usual allies. Democratic Governors from Massachusetts, Illinois and New York — states with large immigrant populations — have decided not to participate in Secure Communities, a fingerprint-sharing program.

Speeding — or Suspending — Deportations

Showing the kinder, gentler side of the administration’s strategy, in August 2011, the White House announced that the Department of Homeland Security would, on a case-by-case basis, suspend deportation proceedings against people who posed no public safety threat. The policy shift has been criticized by some as a backdoor form of the so-called Dream Act — a bill, blocked by Republicans in Congress, that would provide relief to illegal immigrants who were brought to the United States as children and who want to attend college or join the armed forces.

A month later, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency announced that it had arrested 2,901 immigrants with criminal records, highlighting the flip side of the administration’s policy. Officials from the agency portrayed the seven-day sweep, called Operation Cross Check, as the largest enforcement and removal operation in its history. It involved arrests in all 50 states of criminal offenders of 115 nationalities, including people convicted of manslaughter, armed robbery, aggravated assault and sex crimes.

In keeping with both objectives, in November 2011, the Department of Homeland Security announced that it would begin a review of all deportation cases before the immigration courts and start a nationwide training program for enforcement agents and prosecuting lawyers, with the aim of speeding deportations of convicted criminals and halting those of many illegal immigrants with no criminal record.

Taken together, the review and the training, which will instruct immigration agents on closing deportations that fall outside the department’s priorities, are designed to bring sweeping changes to the immigration courts and to enforcement strategies of field agents nationwide.

The approach of deporting some illegal immigrants but not others requires a deep change in the mentality of agents, who have long operated on the principle that any violation was good cause for deportation.

Administration officials said they would proceed case by case using existing legal authorities, and had no plans to exempt any large group of illegal immigrants from deportation.

Background

From the time of the nation’s founding, immigration has been crucial to the United States’ growth and a periodic source of conflict. In recent decades, the country has experienced another great wave of immigration, the largest since the 1920s. However, for the first time, illegal immigrants outnumbered legal ones. The number of illegal immigrants peaked at an estimated 11.9 million in 2008. About 11.2 million illegal immigrants were living in the United States in 2010, a number essentially unchanged from the previous year, a 2011 study showed.

Republicans and Democrats have agreed for years on the need for sweeping changes in the federal immigration laws. President George W. Bush for three years pushed for a bipartisan bill before giving up in 2007 following an outcry from voters opposed to any path to legal status for illegal aliens. During the years that followed, the issue has mostly been dormant, as both parties have been wary of the divisive passions it can arouse.

Immigration Under Bush

In January 2004, President Bush called for an overhaul of the immigration laws, proposing the broadest changes since legislation in 1986 that gave amnesty to more than three million illegal immigrants. Mr. Bush asked Congress to create a guest worker program. Immigrants would be authorized as guest workers for three years, then required to return home. The plan offered illegal immigrants in this country the possibility of becoming legal by registering as temporary workers. After opening the debate, Mr. Bush did not press the issue during his re-election campaign that year.

By 2005, frustration was growing over illegal immigration, particularly among voters in states like Arizona and Georgia that had seen a surge in newcomers. In December 2005, the House passed a bill, championed by conservative Republicans, which focused on law enforcement and border security. Church groups and organizations representing immigrants and Hispanics protested the measure.

In May 2006, the Senate easily passed legislation — crafted primarily by the late Senator Edward M. Kennedy, Democrat of Massachusetts, and by Senator John McCain, Republican of Arizona — that offered a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants and created a guest worker program. But the differences with the House bill proved too great to bridge, and the legislation died. By October of that year Congress, reflecting the changing mood in the country, passed a bill ordering the construction by the end of 2008 of about 700 miles of border fences.

President Bush seized the initiative again in early 2007, convening negotiations among a small bipartisan group of lawmakers, this time including Senator John Kyl, Republican of Arizona, instead of Senator McCain. They wrote an ambitious bill, which was referred to as comprehensive reform, that proposed to open a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants after fees and other penalties, to create a guest worker program and also to re-orient the immigration system to put more emphasis on importing workers and less on family reunification.

That measure encountered intense opposition from well-organized voters who decried it as amnesty for immigrant lawbreakers. It died in June 2007 when it failed to attract enough votes to reach the Senate floor.

In the absence of federal legislation, state legislatures stepped in, adopting 206 laws related to immigration in 2008. The majority of new laws were designed to curb illegal immigration. However, some states sought to aid immigrants with programs to help them learn English and to speed their assimilation in other ways.

On a federal level, officials at Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a branch of the Department of Homeland Security, stepped up raids at factories and in communities.

Immigration Under Obama

Hispanic voters, including many newly naturalized immigrants, helped win several swing states for Barack Obama in 2008. Hispanic groups pressed President Obama to halt workplace raids and to move forward with legislation opening legal pathways for illegal immigrants. But despite early pledges to moderate the Bush administration’s tough policies, the Obama administration pursued an aggressive strategy for an illegal-immigration crackdown.

The Obama administration in August 2009 announced an ambitious plan to overhaul the much-criticized way the nation detains immigration violators, trying to transform it from a patchwork of jail and prison cells to what its new chief called a “truly civil detention system.” The plan aimed to establish more centralized authority over the system, and more direct oversight of detention centers that have come under fire for mistreatment of detainees and substandard — sometimes fatal — medical care.

The government stopped sending families to the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, a former state prison near Austin, Tex., that drew an American Civil Liberties Union lawsuit and scathing news coverage for putting young children behind razor wire.

The decision to stop sending families to Hutto, and to set aside plans for three new family detention centers, was the Obama administration’s clearest departure from its predecessor’s polices. Even so, the Obama administration has embraced many Bush administration policies, including expanding a program to verify worker immigration status that has been widely criticized, bolstering partnerships between federal immigration agents and local police departments, and rejecting a petition for legally binding rules on conditions in immigration detention.

In another enforcement change, the administration replaced immigration raids at factories and farms with a quieter enforcement strategy: sending federal agents to scour companies’ records for illegal immigrant workers.

While the sweeps of the past commonly led to the deportation of such workers, the “silent raids,” as employers call the audits, usually result in the workers being fired, but in many cases they are not deported.

Employers say the audits reach more companies than the work-site roundups of the administration of President George W. Bush. The audits force businesses to fire every suspected illegal immigrant on the payroll — not just those who happened to be on duty at the time of a raid — and make it much harder to hire other unauthorized workers as replacements.

After taking office, Mr. Obama repeated a campaign pledge to offer a comprehensive bill before the end of 2009, and he chose proponents of that approach for senior positions in the administration, notably Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano and Labor Secretary Hilda Solis. But the deep recession, with millions of Americans losing jobs, dimmed the political prospects for efforts to increase immigration, and groups opposing legalization remained confident they could block any such proposal.

In broad outlines, officials said, the Obama administration favored legislation that would bring illegal immigrants into the legal system by recognizing that they violated the law, and imposing fines and other penalties to fit the offense. The legislation would seek to prevent future illegal immigration by strengthening border enforcement and cracking down on employers who hire illegal immigrants, while creating a national system for verifying the legal immigration status of new workers.

Activity Swings Toward the States

With little movement toward federal immigration reform in recent years, individual states have churned out legislation.

Immigration certainly got the nation’s attention in 2010 after the passage of an Arizona statute. On July 28, 2010, one day before the law was to take effect, a federal judge blocked Arizona from enforcing the statute’s most controversial provisions, including sections that called for officers to check a person’s immigration status while enforcing other laws and that required immigrants to carry their papers at all times.

The Obama administration challenged parts of the law in court, saying that it could not be reconciled with federal immigration laws and policies. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, in San Francisco, blocked enforcement of parts of the law in April 2011. In December, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the Arizona case.

In urging the court to hear the case, Arizona v. United States, No. 11-182, Paul D. Clement, representing Arizona, said the state law did not conflict with but, rather, complemented federal policies. In a brief urging the Supreme Court not to hear the case, Donald B. Verrilli Jr., the United States solicitor general, said this provision created a state “crime of being unlawfully present in the United States.”

During the time that Arizona’s law was blocked, the center of activity on immigration moved elsewhere. Legislative leaders in at least half a dozen states said they would propose bills similar to Arizona’s law, and have announced measures to limit access to public colleges and other benefits for illegal immigrants and to punish employers who hire them. And at least five states have agreed on an unusual coordinated effort to cancel automatic United States citizenship for children born in this country to illegal immigrant parents.

Opponents say that the effort would be unconstitutional, arguing that the power to grant citizenship resides with the federal government, not with the states.

In September 2011, a federal judge upheld most sections of Alabama’s far-reaching immigration law that had been challenged by the Obama administration, including portions that had been blocked in other states.

The decision, by Judge Sharon Lovelace Blackburn of Federal District Court in Birmingham, made it more likely that the fate of the recent flurry of state laws against illegal immigration would be decided by the Supreme Court. It also means that Alabama now has by far the strictest such law of any state, going further than the one passed in Arizona.

The judge issued a preliminary injunction against several sections of the law, agreeing with the government’s case that they pre-empted federal law. She blocked a broad provision that outlawed the harboring or transporting of illegal immigrants and another that barred illegal immigrants from enrolling in or attending public universities.

The judge upheld a section that requires state and local law enforcement officials to try to verify a person’s immigration status during routine traffic stops or arrests, if “a reasonable suspicion” exists that the person is in the country illegally. And she ruled that a section that criminalized the “willful failure” of a person in the country illegally to carry federal immigration papers did not pre-empt federal law.

Privately Run Immigration Detention System

In the United States and elsewhere, including Britain and Australia, the use of private security companies has turned the detention of unwanted immigrants into a multinational industry. Increasingly, governments are looking to private companies to expand detention and show voters that they are enforcing tougher immigration laws.

Some of the companies are huge — one is among the largest private employers in the world — and they say they are meeting demand faster and less expensively than the public sector could.

But the ballooning of privatized detention has been accompanied by scathing inspection reports, lawsuits and the documentation of widespread abuse and neglect, sometimes lethal. Human rights groups say detention has neither worked as a deterrent nor speeded deportation, as governments contend, and some worry about the creation of a “detention-industrial complex” with a momentum of its own.

Private companies now control nearly half of all detention beds in the United States. In Britain, 7 of 11 detention centers and most short-term holding places for immigrants are run by for-profit contractors.

No country has more completely outsourced immigration enforcement, with more troubled results, than Australia. Under unusually severe mandatory detention laws, the system has been run by a succession of three publicly traded companies since 1998.