Thin Line for Group of Muslims in Egypt

페이지 정보

작성자 관리자 작성일작성일 10-09-06 수정일수정일 70-01-01 조회6,433회관련링크

본문

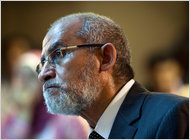

<Mohammed Badie, the supreme guide of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, listened to complaints in August in Cairo.>

Thin Line for Group of Muslims in Egypt

By THANASSIS CAMBANIS

One by one, the guests at the Muslim Brotherhood’s annual Ramadan iftar banquet strode to the rostrum. A who’s who of Egypt’s opposition began hectoring the Islamist group. The Brotherhood, they said, by far the most muscular and influential of Egypt’s dissident organizations, should withdraw from the coming parliamentary election that would most certainly be rigged by the authoritarian government.

“Why won’t you take the initiative?” shouted Karima El-Hefnawi, a secular activist and leader of the popular Kifaya protest movement. “Why won’t the Muslim Brotherhood boycott this farce?” The supreme guide of the Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie, sat uncomfortably a few feet to her right.

At the close of the evening, Mr. Badie was noncommittal. The Brotherhood, he said, in time would make up its mind: “Haste makes waste.”

The Muslim Brotherhood is engaged in a delicate dance. Despite all efforts to marginalize the Islamist organization by the United States and its close ally, the Egyptian government, it remains the most credible opposition group. Some of its members want the Brotherhood to fight the government head on, but the Islamist leadership has other goals: freedom to proselytize and organize in neighborhoods, and in the long term, a lifting of the official government ban on its activities.

With an end in sight to President Hosni Mubarak’s 29-year reign, the Brotherhood appears to be signaling its willingness to cut a deal with Mr. Mubarak’s potential successors by not overtly challenging the ruling party’s monopoly on power.

In a widely noted shift in tactics, the Muslim Brotherhood has joined forces with the secular opposition, taking charge of a petition drive to demand that the government lift the state of emergency and reform election rules.

The Brotherhood as of Sunday afternoon had collected 653,657 signatures to secular parties’ 106,661.

The groups aim to gather one million names before Ramadan ends Friday.

Secular groups mistrust the Brotherhood, which they say is more interested in muscling aside smaller opposition parties than in demanding an end to the National Democratic Party’s emergency rule.

“We are forced to come together,” said Hassan Nafaa, a political scientist at Cairo University and the head of the National Association for Change.

His organization wants a secular, free political system based on Egypt’s existing, if often ignored, Constitution, but he recognizes that the opposition needs the Brotherhood’s disciplined rank and file to have any chance at success. So for the time being, he is willing to ignore their differences. “No one will be able to change the system alone,” Mr. Nafaa said.

Mohamed ElBaradei, the Nobel laureate and former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, briefly energized the secular opposition this spring, when he said he would consider a presidential run if the rules were changed to allow a fair challenge to Mr. Mubarak. He founded the National Association for Change, an umbrella group that includes the Brotherhood.

Since then, however, Dr. ElBaradei has been largely absent, spending his summer abroad and communicating with his frustrated followers by Twitter. He returned to Egypt for a visit on Wednesday.

The government has dismissed the petition campaign as political theater, and even opposition leaders voice skepticism. “How many of these 700,000 would actually go down to the streets?” one organizer said.

Most observers, including the Brotherhood’s own legislators, are convinced that the government will manipulate the elections expected in October or November to reduce the Islamists’ share in Parliament. Currently the Brotherhood has the largest opposition bloc — 88 seats, about 20 percent of the total.

Since the 2005 parliamentary election, which was marred by allegations of fraud and police intimidation, the government has abolished judicial oversight of elections, making a fair vote even more unlikely, according to civil society groups and opposition parties.

In June, the Muslim Brotherhood did not win a single seat in elections for the Shura Council, the upper house of Parliament, and there were reports of widespread violence and vote tampering. Despite its visible support base in urban areas and the Nile Delta villages, the Brotherhood does not hold even one of the approximately 50,000 municipal council seats nationwide.

<The New York Times>,2010/09/

Thin Line for Group of Muslims in Egypt

By THANASSIS CAMBANIS

One by one, the guests at the Muslim Brotherhood’s annual Ramadan iftar banquet strode to the rostrum. A who’s who of Egypt’s opposition began hectoring the Islamist group. The Brotherhood, they said, by far the most muscular and influential of Egypt’s dissident organizations, should withdraw from the coming parliamentary election that would most certainly be rigged by the authoritarian government.

“Why won’t you take the initiative?” shouted Karima El-Hefnawi, a secular activist and leader of the popular Kifaya protest movement. “Why won’t the Muslim Brotherhood boycott this farce?” The supreme guide of the Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie, sat uncomfortably a few feet to her right.

At the close of the evening, Mr. Badie was noncommittal. The Brotherhood, he said, in time would make up its mind: “Haste makes waste.”

The Muslim Brotherhood is engaged in a delicate dance. Despite all efforts to marginalize the Islamist organization by the United States and its close ally, the Egyptian government, it remains the most credible opposition group. Some of its members want the Brotherhood to fight the government head on, but the Islamist leadership has other goals: freedom to proselytize and organize in neighborhoods, and in the long term, a lifting of the official government ban on its activities.

With an end in sight to President Hosni Mubarak’s 29-year reign, the Brotherhood appears to be signaling its willingness to cut a deal with Mr. Mubarak’s potential successors by not overtly challenging the ruling party’s monopoly on power.

In a widely noted shift in tactics, the Muslim Brotherhood has joined forces with the secular opposition, taking charge of a petition drive to demand that the government lift the state of emergency and reform election rules.

The Brotherhood as of Sunday afternoon had collected 653,657 signatures to secular parties’ 106,661.

The groups aim to gather one million names before Ramadan ends Friday.

Secular groups mistrust the Brotherhood, which they say is more interested in muscling aside smaller opposition parties than in demanding an end to the National Democratic Party’s emergency rule.

“We are forced to come together,” said Hassan Nafaa, a political scientist at Cairo University and the head of the National Association for Change.

His organization wants a secular, free political system based on Egypt’s existing, if often ignored, Constitution, but he recognizes that the opposition needs the Brotherhood’s disciplined rank and file to have any chance at success. So for the time being, he is willing to ignore their differences. “No one will be able to change the system alone,” Mr. Nafaa said.

Mohamed ElBaradei, the Nobel laureate and former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, briefly energized the secular opposition this spring, when he said he would consider a presidential run if the rules were changed to allow a fair challenge to Mr. Mubarak. He founded the National Association for Change, an umbrella group that includes the Brotherhood.

Since then, however, Dr. ElBaradei has been largely absent, spending his summer abroad and communicating with his frustrated followers by Twitter. He returned to Egypt for a visit on Wednesday.

The government has dismissed the petition campaign as political theater, and even opposition leaders voice skepticism. “How many of these 700,000 would actually go down to the streets?” one organizer said.

Most observers, including the Brotherhood’s own legislators, are convinced that the government will manipulate the elections expected in October or November to reduce the Islamists’ share in Parliament. Currently the Brotherhood has the largest opposition bloc — 88 seats, about 20 percent of the total.

Since the 2005 parliamentary election, which was marred by allegations of fraud and police intimidation, the government has abolished judicial oversight of elections, making a fair vote even more unlikely, according to civil society groups and opposition parties.

In June, the Muslim Brotherhood did not win a single seat in elections for the Shura Council, the upper house of Parliament, and there were reports of widespread violence and vote tampering. Despite its visible support base in urban areas and the Nile Delta villages, the Brotherhood does not hold even one of the approximately 50,000 municipal council seats nationwide.

<The New York Times>,2010/09/