China’s Intimidation of Dissidents Said to Persist After Prison

페이지 정보

작성자 관리자 작성일작성일 11-02-19 수정일수정일 70-01-01 조회8,192회관련링크

본문

China’s Intimidation of Dissidents Said to Persist After Prison

Du Bin for The New York Times

DONGSHIGU, China — Chen Guangcheng is officially a free man but it is hard to imagine a life more constrained. One of the country’s most prominent rights defenders, Mr. Chen is confined to his home 24 hours a day by security agents and hired peasant men armed with sticks, bricks and walkie-talkies. Visitors who try to see him are physically repulsed and sometimes beaten. Blinding floodlights illuminate his stone farmhous

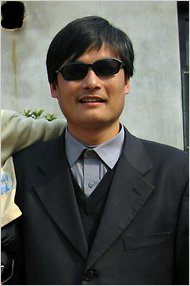

Chen Guangcheng, a Chinese human rights activist, outside a house in Shandong province in 2005.

With Internet and phone service blocked, he has no contact with the outside world. And the punishment is not his alone: Mr. Chen’s wife and young daughter have been subjected to the same restrictions since he emerged from a 51-month prison sentence last September, widely viewed as retribution for his advocacy efforts against a local family planning campaign of forced abortions and sterilizations.

“I have come out of a small jail and walked into a bigger jail,” Mr. Chen, 39, a blind, self-educated lawyer, said in a homemade video that was smuggled out of his village last week. “What they are doing is thuggery.”

Euphemistically known as “ruanjin,” or soft detention, Mr. Chen’s house arrest is an increasingly common tactic employed by the Chinese authorities as they seek to extend their control over lawyers, democracy activists and underground church leaders who refuse to bend to their will, human rights advocates say.

Though Chinese authorities deny the existence of such measures, Communist Party security officials appear to be expanding the use of extended home confinement, abductions and in some cases assault or torture against a broadening array of perceived enemies, according to rights advocates and legal experts. One group, Chinese Human Rights Defenders, logged more than 3,500 cases of arbitrary detention last year, a category that includes people held in so-called black jails or in psychiatric hospitals.

Beyond confining Mr. Chen, the authorities are mobilizing to choke a resurgence of activism supporting him. On Wednesday, the police in Beijing blocked a number of rights campaigners from attending a strategy session and assaulted one lawyer, Jiang Tianyong, at a stationhouse, he said.

The campaign of extrajudicial intimidation seems to have taken an especially heavy toll on political prisoners who had previously been released, among them Zheng Enchong, a lawyer in Shanghai who has spent the last four years virtually confined to his 14th floor apartment, and Gao Zhisheng, a once-fearless defender of dispossessed peasants who has been abducted several times and is presumed to be in the custody of state security personnel. Before he disappeared again last year, Mr. Gao told The Associated Press that he had been repeatedly brutalized during 14 months in captivity.

Liu Xia, the wife of Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, has not been seen since the prize was announced last October. Ni Yulan, a lawyer in Beijing who was left crippled by a police beating in 2002, says security officials arranged for water and electricity to be cut off from the hotel room she shares with her husband in an effort to force them onto the streets.

“Making lawyers disappear and subjecting dissidents to constant harassment makes it hard to take seriously the government’s claims that it is devoted to rule of law,” said Jerome A. Cohen, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and an expert on Chinese law.

In recent decades, even as it tentatively embraced Western-style legal reforms, the Communist Party never completely shed its reliance on extralegal tactics to rein in critics. Former political prisoners could expect tightened confinement during important state occasions, and practitioners of Falun Gong, the banned spiritual movement, were regularly sent to labor camps if they refused to renounce their faith. Over the years, human rights advocates say that scores have died in detention.

But during the last five years, legal scholars say the country’s powerful security apparatus has leveraged events like the Olympics and a spike in social unrest to institute more sweeping measures and fatten policing budgets.

“The police are progressively trying new techniques, and it seems that Beijing is ready to go along,” said Nicholas Bequelin, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch in Hong Kong. “We used to worry about people getting arrested and losing their jobs. Now we have to worry about them losing their lives.”

Legal experts say that even though Communist Party leaders down the line have ultimate control over the police, the prosecutors and the courts, they face mounting internal pressure and incentives to quash threats to stability at the grassroots, often making it more expedient to circumvent the legal system with highly intrusive surveillance or temporary disappearances.

Teng Biao, a lecturer at China University of Political Science and Law, said security officials were partly responding to the surge in popular activism that, despite their best efforts at censorship, manages to bubble up through the Internet. Questioning and arresting the growing ranks of well-educated and wired activists, he said, can be a bureaucratic headache for those charged with maintaining internal security. Instead they resort to stealth.

“There are too many people doing too many different things and the authorities know if they use so-called legal methods, it will only provoke a greater domestic backlash and more international pressure,” he said.

Mr. Teng says he has had first hand experience with extrajudicial punishment on numerous occasions in recent years, including a “disappearance” last October during which he was pummeled and kicked by police officers who repeatedly reminded him they were above the law. “Let’s beat him to death and dig a hole to bury him,” one officer said to another, according to an account he published.

Officials are also increasing their use of collective family punishment, legal experts say, a practice rooted in imperial China that destroyed countless families during the Cultural Revolution. The relatives of dissidents are periodically kept under house arrest, as in the case of Zeng Jinyan, the wife of imprisoned rights activist Hu Jia, or they are subjected to travel bans.

In December, the public security bureau in Beijing told Ilham Tohti, an outspoken critic of Chinese rule in Xinjiang, that his daughter would not be allowed to go overseas to attend the American school where she planned to study English.

The authorities in Shandong Province appear to have spared little expense in their confinement of Mr. Chen and his family, setting aside millions of dollars, according to figures publicized by his wife, to pay for surveillance cameras, cellphone signal-blocking equipment and rotating crews of dozens of men who guard all entrances to tiny Dongshigu village.

It was unclear who smuggled out the video, but China Aid, a Christian organization in Texas that posted it online last week, credited a “sympathetic government source.” In it, Mr. Chen’s wife, Yuan Weijing, bleakly described the strictures of their existence: men peer through their windows or barge in unannounced; at night, an iron rod keeps them locked indoors.

Under Close Watch This car, with tinted windows and covered license plates, trailed reporters and a photographer from The New York Times for over 15 miles after they had been chased out of Dongshigu.

Her elderly parents and her son cannot visit, her young daughter cannot attend school and her husband, who suffers from chronic diarrhea, has been prevented from seeing a doctor.

Human rights groups say the couple was badly beaten after the video became public. In it, Mr. Chen said local officials told him that their goal was to provoke him into stepping over some invisible line, providing a legal pretext for his return to jail.

“If they merely say you are guilty, then you are guilty,” he said.

His contention is not far fetched. In 2006, after a flock of supporters held a protest against his house arrest, he himself was convicted of blocking traffic and destroying public property.

The authorities deny that the family is under any restrictions. Confronted by European diplomats, Chinese officials have insisted there is no such thing as house arrest in China. Reached by phone on Wednesday, Xue Jie, the director of the Yinan County propaganda bureau, suggested that a reporter could simply call Mr. Chen or just drop by.

But those who try to visit him encounter a very different reality. Gao Xinbo, 33, a veteran supporter of Mr. Chen who sneaked into the village Monday night, said he was pummeled senseless, robbed of money and his cellphone, and dumped on a dark road 40 miles away. Last December, Western diplomats were jostled and forcibly searched before guards forced them to flee.

Earlier this week, several journalists, including reporters and a photographer from The New York Times, were roughed up by a dozen or so men who menaced them with sticks and confiscated their camera chips. The men wore plain clothes and refused to show identification as they tried to erase photographs and video footage.

Asked what law authorized their actions, one of them grunted dismissively. “This has nothing to do with law,” he said.

<The NewYork Times>,2011/02/19

Du Bin for The New York Times

DONGSHIGU, China — Chen Guangcheng is officially a free man but it is hard to imagine a life more constrained. One of the country’s most prominent rights defenders, Mr. Chen is confined to his home 24 hours a day by security agents and hired peasant men armed with sticks, bricks and walkie-talkies. Visitors who try to see him are physically repulsed and sometimes beaten. Blinding floodlights illuminate his stone farmhous

Chen Guangcheng, a Chinese human rights activist, outside a house in Shandong province in 2005.

With Internet and phone service blocked, he has no contact with the outside world. And the punishment is not his alone: Mr. Chen’s wife and young daughter have been subjected to the same restrictions since he emerged from a 51-month prison sentence last September, widely viewed as retribution for his advocacy efforts against a local family planning campaign of forced abortions and sterilizations.

“I have come out of a small jail and walked into a bigger jail,” Mr. Chen, 39, a blind, self-educated lawyer, said in a homemade video that was smuggled out of his village last week. “What they are doing is thuggery.”

Euphemistically known as “ruanjin,” or soft detention, Mr. Chen’s house arrest is an increasingly common tactic employed by the Chinese authorities as they seek to extend their control over lawyers, democracy activists and underground church leaders who refuse to bend to their will, human rights advocates say.

Though Chinese authorities deny the existence of such measures, Communist Party security officials appear to be expanding the use of extended home confinement, abductions and in some cases assault or torture against a broadening array of perceived enemies, according to rights advocates and legal experts. One group, Chinese Human Rights Defenders, logged more than 3,500 cases of arbitrary detention last year, a category that includes people held in so-called black jails or in psychiatric hospitals.

Beyond confining Mr. Chen, the authorities are mobilizing to choke a resurgence of activism supporting him. On Wednesday, the police in Beijing blocked a number of rights campaigners from attending a strategy session and assaulted one lawyer, Jiang Tianyong, at a stationhouse, he said.

The campaign of extrajudicial intimidation seems to have taken an especially heavy toll on political prisoners who had previously been released, among them Zheng Enchong, a lawyer in Shanghai who has spent the last four years virtually confined to his 14th floor apartment, and Gao Zhisheng, a once-fearless defender of dispossessed peasants who has been abducted several times and is presumed to be in the custody of state security personnel. Before he disappeared again last year, Mr. Gao told The Associated Press that he had been repeatedly brutalized during 14 months in captivity.

Liu Xia, the wife of Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, has not been seen since the prize was announced last October. Ni Yulan, a lawyer in Beijing who was left crippled by a police beating in 2002, says security officials arranged for water and electricity to be cut off from the hotel room she shares with her husband in an effort to force them onto the streets.

“Making lawyers disappear and subjecting dissidents to constant harassment makes it hard to take seriously the government’s claims that it is devoted to rule of law,” said Jerome A. Cohen, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and an expert on Chinese law.

In recent decades, even as it tentatively embraced Western-style legal reforms, the Communist Party never completely shed its reliance on extralegal tactics to rein in critics. Former political prisoners could expect tightened confinement during important state occasions, and practitioners of Falun Gong, the banned spiritual movement, were regularly sent to labor camps if they refused to renounce their faith. Over the years, human rights advocates say that scores have died in detention.

But during the last five years, legal scholars say the country’s powerful security apparatus has leveraged events like the Olympics and a spike in social unrest to institute more sweeping measures and fatten policing budgets.

“The police are progressively trying new techniques, and it seems that Beijing is ready to go along,” said Nicholas Bequelin, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch in Hong Kong. “We used to worry about people getting arrested and losing their jobs. Now we have to worry about them losing their lives.”

Legal experts say that even though Communist Party leaders down the line have ultimate control over the police, the prosecutors and the courts, they face mounting internal pressure and incentives to quash threats to stability at the grassroots, often making it more expedient to circumvent the legal system with highly intrusive surveillance or temporary disappearances.

Teng Biao, a lecturer at China University of Political Science and Law, said security officials were partly responding to the surge in popular activism that, despite their best efforts at censorship, manages to bubble up through the Internet. Questioning and arresting the growing ranks of well-educated and wired activists, he said, can be a bureaucratic headache for those charged with maintaining internal security. Instead they resort to stealth.

“There are too many people doing too many different things and the authorities know if they use so-called legal methods, it will only provoke a greater domestic backlash and more international pressure,” he said.

Mr. Teng says he has had first hand experience with extrajudicial punishment on numerous occasions in recent years, including a “disappearance” last October during which he was pummeled and kicked by police officers who repeatedly reminded him they were above the law. “Let’s beat him to death and dig a hole to bury him,” one officer said to another, according to an account he published.

Officials are also increasing their use of collective family punishment, legal experts say, a practice rooted in imperial China that destroyed countless families during the Cultural Revolution. The relatives of dissidents are periodically kept under house arrest, as in the case of Zeng Jinyan, the wife of imprisoned rights activist Hu Jia, or they are subjected to travel bans.

In December, the public security bureau in Beijing told Ilham Tohti, an outspoken critic of Chinese rule in Xinjiang, that his daughter would not be allowed to go overseas to attend the American school where she planned to study English.

The authorities in Shandong Province appear to have spared little expense in their confinement of Mr. Chen and his family, setting aside millions of dollars, according to figures publicized by his wife, to pay for surveillance cameras, cellphone signal-blocking equipment and rotating crews of dozens of men who guard all entrances to tiny Dongshigu village.

It was unclear who smuggled out the video, but China Aid, a Christian organization in Texas that posted it online last week, credited a “sympathetic government source.” In it, Mr. Chen’s wife, Yuan Weijing, bleakly described the strictures of their existence: men peer through their windows or barge in unannounced; at night, an iron rod keeps them locked indoors.

Under Close Watch This car, with tinted windows and covered license plates, trailed reporters and a photographer from The New York Times for over 15 miles after they had been chased out of Dongshigu.

Her elderly parents and her son cannot visit, her young daughter cannot attend school and her husband, who suffers from chronic diarrhea, has been prevented from seeing a doctor.

Human rights groups say the couple was badly beaten after the video became public. In it, Mr. Chen said local officials told him that their goal was to provoke him into stepping over some invisible line, providing a legal pretext for his return to jail.

“If they merely say you are guilty, then you are guilty,” he said.

His contention is not far fetched. In 2006, after a flock of supporters held a protest against his house arrest, he himself was convicted of blocking traffic and destroying public property.

The authorities deny that the family is under any restrictions. Confronted by European diplomats, Chinese officials have insisted there is no such thing as house arrest in China. Reached by phone on Wednesday, Xue Jie, the director of the Yinan County propaganda bureau, suggested that a reporter could simply call Mr. Chen or just drop by.

But those who try to visit him encounter a very different reality. Gao Xinbo, 33, a veteran supporter of Mr. Chen who sneaked into the village Monday night, said he was pummeled senseless, robbed of money and his cellphone, and dumped on a dark road 40 miles away. Last December, Western diplomats were jostled and forcibly searched before guards forced them to flee.

Earlier this week, several journalists, including reporters and a photographer from The New York Times, were roughed up by a dozen or so men who menaced them with sticks and confiscated their camera chips. The men wore plain clothes and refused to show identification as they tried to erase photographs and video footage.

Asked what law authorized their actions, one of them grunted dismissively. “This has nothing to do with law,” he said.

<The NewYork Times>,2011/02/19